If you know that you have endogamy in your family tree due to many generations of marriages between cousins, you might want to know how this affects your DNA and matches. In this post, learn more about this topic through examples.

Some people might initially think that having endogamy in their family tree is a bit odd. In truth, it’s very normal.

Most of us have endogamy in our ancestry, especially if we look back far enough.

Are you not exactly sure if you have endogamy? If you see places in your tree where first, second, and third cousins are marrying each other over the course of multiple generations, then you see endogamy.

One single instance of cousins marrying each other is not sufficient to be endogamy, which is the practice of marrying within ones local community or greater clan where most members are closely or distantly related to each other. Instead, we call a single cousin marriage an occurrence of “pedigree collapse“.

Now, how does all of this affect your DNA and your DNA matches?

As you might have guessed, endogamy does make analyzing and learning from DNA matches a bit more complex. The most important thing is to understand exactly how endogamy is affecting the DNA that you share with your matches.

Endogamy means you are related to many DNA matches in more than one way

If you have endogamy in your tree, then you will be related to your DNA matches from that line of your tree in several different ways. This is because you share different sets of common ancestors, meaning you will have more than one type of cousin relationship with the same DNA match.

To describe this concept using a pretend example, let’s say that your father is from an endogamous population and your mother is not. Both of your paternal grandparents belong to this same community where there have been generations of distant cousins marrying each other over the course of several generations.

Now, take a look at a DNA match from your father’s side of the family. You might notice that you share a set of fourth and sixth great-grandparents from your paternal grandmother’s line, and third and fifth great-grandparents from your paternal grandfather’s line.

This would mean that you are 5th and 7th cousins from your grandmother’s side of the family, and 4th and 6th cousins on your paternal grandfather’s side of the tree.

Hypothetical example of endogamy in a family tree

It can be confusing to visualize how it is possible to have more than one cousin relationship with a DNA match on the same line of your family tree. In genealogy, we typically focus on the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), which means we tend to ignore these other ways that we might be related to a person.

The reason that we usually give more importance to the MRCA is because the most recent ancestor indicates the most significant relationship among multiple potential relationships, and because the DNA we share with a relative is more likely to have been inherited from our more recent ancestors.

However, when we have endogamy in our tree, we need to examine the possibility of more distant relationships along with the closer one.

To illustrate an example of how endogamy could play out in a family tree, I put a sample from my own family tree below and have highlighted three sets of common ancestors that I share with a hypothetical DNA match. Elizabeth Simmons is my ancestor through my paternal grandmother, but I will pretend that she is my grandmother for this example.

I have indicated John Simmons and Mercy Paebody as the set of most recent common ancestors that I share with my DNA match. If my relative is the same number of generations descended from this set of common ancestors, our closest relationship would be 5th cousins.

However, we see that there are two other couples highlighted. While all three of the shared ancestors are on Elizabeth’s father’s side of the family tree, we can see that the ancestors are related to Elizabeth through different lines of her tree:

- John Simmons and Mercy Paebody are her 3rd great-grandparents on her paternal grandfather’s line

- John and Ann Norton are her 4th great-grandparents on her paternal grandfather’s line, but they are not the parents of her 3rd great-grandparents on that line, which is key

- Heinrich and Anna Tallman are her 4th great-grandparents on her paternal grandmother’s side of the tree

Since her DNA match shares all of these ancestors in common, we should understand that the DNA match is descended from a different child of each of the set of common ancestors, also known as a collateral line of the family tree. That means my DNA match is descended from a sister of Peter Tallman, a brother of Mary Tucker, and a sister of William Simmons.

The fact of my DNA match being related to me in more than one way doesn’t automatically make it endogamy. However, if we imagine that all three of the pairs of common ancestors that I highlighted in red are second or third cousins to each other, which they may have been, we would have evidence of some endogamy.

Since both myself and my DNA match would DNA segments matching each of these six total ancestors, we would both likely share many smaller segments inherited from several of their ancestors. The total number of DNA segments shared would be larger than the typical number of DNA segments shared between fifth cousins, which is our closest cousin relationship.

In addition, the total amount of DNA that we share would equal an amount not typically seen between fifth cousins.

The portion of my tree I used for this example is from colonial times in the United States, prior to independence from Britain. It is very common to find endogamy and pedigree collapse in this population because there was a limited “founding population”, and so families tended to intermarry over long periods of time.

Due to increased immigration to the United States during the 1800s and domestic migration patterns, people had more variety in choices for partners and endogamy decreased.

Endogamy means you will have to look further back in your tree for a common ancestor than your shared DNA may indicate

If you have a lot of endogamy in your family tree, you will share multiple DNA segments with many of your matches. In addition, you may also have many DNA matches who share a relatively high number of centimorgans with you, but you may not be able to figure out your connection to them.

For example, you might have a DNA match that shares 128 centimorgans with you. Without endogamy present, we would expect to have to look no further back than great-great grandparents to find a common ancestor shared with this match.

If this match is on your endogamous lines, you both could have accurate trees going back to second or third great-grandparents on all lines and not see the common ancestor.

The explanation is that you and your match are related to each other in multiple ways. Your high number of shared centimorgans is due to both of you having inherited segments of DNA from many of your shared ancestors.

In order to identify all of the ways you are related to your match in this case, you would have to look further back in both of your family trees than the second or third great-grandparent level.

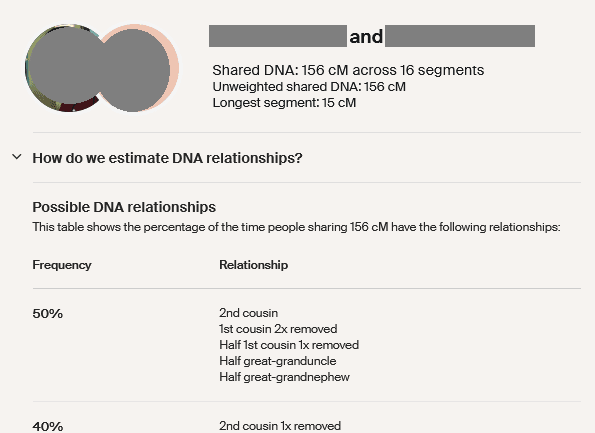

A good example of endogamy in a DNA match is my husband’s closest DNA match on Ancestry. Both of my husband’s parents come from a small community in Mexico where people married within the local community for likely hundreds of years.

In addition, my husband is Indigenous American, with about 95% of his DNA matching the Indigenous Americas region on Ancestry. Since he shares a common ancestry with many other indigenous groups, small identical segments of DNA have been passed down from very distant ancestors.

Ancestry reports that my husband and his DNA match share 156 cMs across 16 segments. 156 cMs would generally indicate a pretty close match, and Ancestry agrees – they suggest a second cousin match.

However, I can tell that this person is not my husband’s second cousin because the longest segment is only 15 cMs long. This short longest segment indicates a much more distant relationship.

In addition, the number of segments (16!) means that all of the other segments are shorter than 15 cMs. Most likely, all of the small segments were inherited from different distant ancestors.

Distant endogamy in your family tree has less of an effect on your matches

If the endogamy in your family tree is more than 10 or so generations back, the effect on your DNA and matches is going to be less noticeable.

A common ancestor 10 generations ago takes us back to our 8th great-grandparents. Cousins who are also descended from those 8th great-grandparents are our ninth cousins, and we share DNA with about a .0034, or a third of one percent, of those ninth cousins.

This means that even if we share multiple sets of 8th great-grandparents with a 9th cousin, we would still have a very low chance of finding that cousin on our DNA match list.

However, you might have a situation where you have multiple relationships with a DNA match, and a few of those relationships are very distant (like a 9th cousin!) and others are closer. In this situation, you should consider the more likely scenario that your shared DNA was inherited from your more recent shared ancestors.

The good news is that most of us don’t have family trees going back on all lines far enough to identify many of our ninth cousins – or even eighth cousins, for that matter!

What if both of your parents have endogamy from the same region or community?

If both of your parents are from the same community where you are finding evidence of endogamy, then you should consider the possibility that your parents could be distantly related to each other. This means that you could have DNA matches that are related to you on both the maternal and paternal lines of your family tree.

This can present a few difficulties in analyzing DNA matches because we often use “shared matches” or matches that we share in common with a particular match, to try to figure out if they are related on our mother or father’s line of the family.

If you are curious about whether your parents may have been related to each other in some way, you can upload your DNA to Gedmatch and use the “Are Your Parents Related?” tool. If you have inherited DNA from each parent that is identical on both copies of your chromosomes, then this is a good indicator that your parents may have had shared ancestry.

Conclusion

I hope that you have learned more about endogamy in this post and that you now understand how endogamy can affect your DNA match lists.

If you have any questions about something that you read here, or if you would like to ask a specific question about endogamy that you have seen in your family tree, please join in the discussion below.

Thanks for reading today!