You might already know that you can find basic information about your ancestors in old census records. However, there are some aspects of the census that might surprise you - and help you learn things you never knew possible about your ancestors.

The United States has conducted a census every ten years since 1790. The goal of the census is to count the population and learn important information about the people living here.

Each census year saw a different form being used, with slightly different questions. The earlier censuses only asked for the name of the head of household, while the newer forms wanted the names of everyone living in the home.

Along with this basic information, other details were often collected by enumerators, or the people who collected the census data. We are lucky to be able to have access from these brief snapshots of our ancestor's lives, since all records 72 years and older have been digitized and indexed (except the 1890 census).

Below, I go into detail about some of the things you might be surprised to learn about the census records.

Not everyone was counted in the census

While the goal of the census was to count everyone, this has never actually happened. Many people are missed each census year.

For example, it is estimated that 1,260,078 people were not counted in the 1870 census. Native Americans, African-Americans, and young children were the most commonly under-counted, but many white families were missed, as well.

During the 1860 census and prior, census records reveal the reality of legal slavery in the United States. Enslaved people were often counted on the census, but not listed individually.

In addition, some families might be missing from the available census records even if they were counted during the actual census taking. Mistakes may have occurred during the microfilming or digitization process, which could have included skipping pages while scanning (i.e. flipping two pages instead of two).

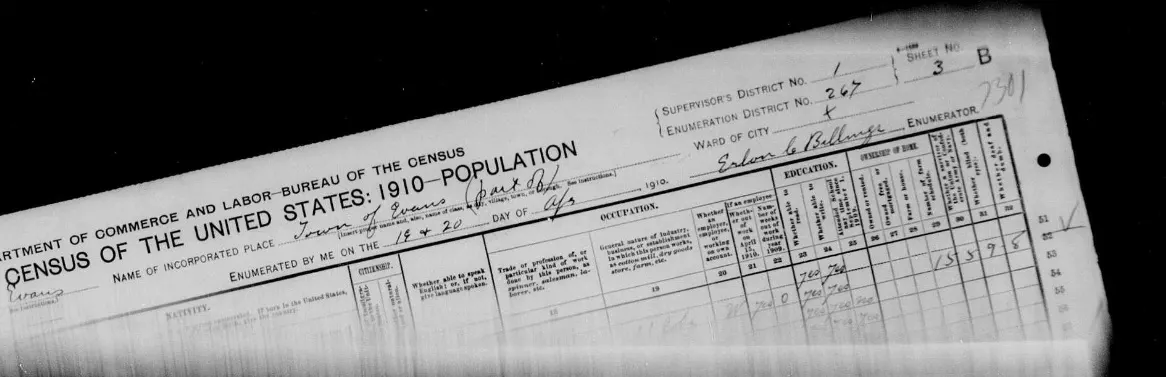

The image below is from the 1910 census records in Colorado. The page wasn't straight when it was put onto microfilm, so it is possible that the information on this page is no longer available for anyone to see.

Unfortunately, many of the original census records were destroyed after the microfilming process. Those that still exist might have been given to universities and libraries, so if you are interested in a specific collection, you will have to try to figure out exactly what happened to the original sheets.

Fortunately, there are many copies of the original microfilms. If you want to go through microfilm images to see if your ancestor may have been counted (and just not indexed correctly), you still have this option.

You can read about the National Archives Census Microfilm Catalogs or find other ways to view the microfilms.

Mistakes were common

Census records are filled with mistakes. Dates of birth can be incorrect, names could be spelled wrong, genders could be mixed up, among many other mistakes.

There are many reasons for mistakes on the census. There could have been a language barrier, or the person giving the information may not have known accurate details.

Unfortunately, there is no way to go back and correct information that is wrong. On some websites, there are fields for correcting information or adding notes in that site's index of the census, but this does not correct the actual census record.

You can also make notes on your family tree when you add a record, for future reference or for others to see.

People sometimes lied to the census taker

Sometimes, people were not truthful when questioned by the census taker. To me, this is different than a "mistake", which is why I included it in a different section.

I know that people lie on census records because I remember a coworker telling me that they intentionally left off some important details on the 2000 census when they filled it out. I was just a teenager at the time, so I didn't really understand the importance of an accurate census.

If this happened at least once in 2000, I'm sure it happened numerous times since 1790.

It's very difficult, however, to distinguish between lies and information that is accidentally wrong, for whatever reason.

Your ancestor may have been selected to provide additional details

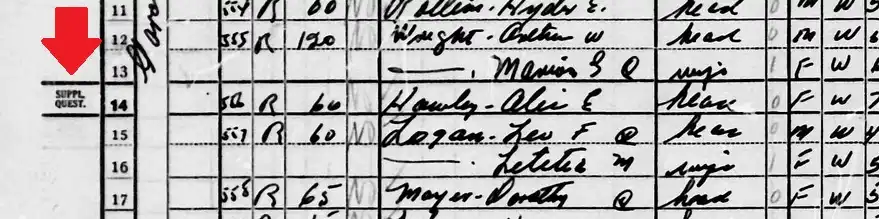

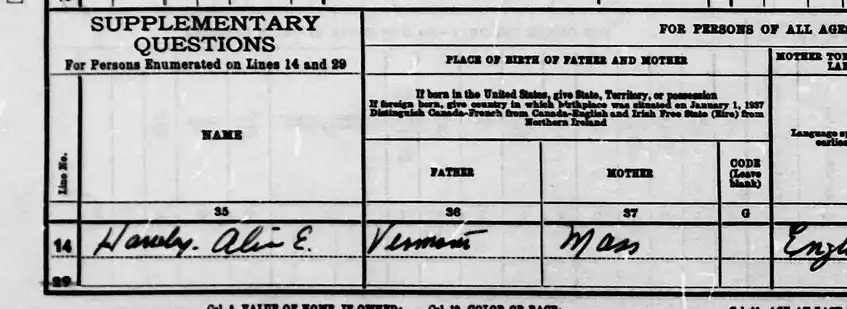

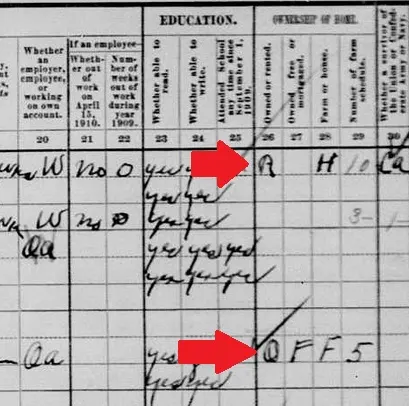

Some census years, most notably for the 1940 and 1950 census, people were selected to provide additional information for the census. The way to know if your ancestor was chosen is to see if their name is written on a line that is specially marked "supp. question" (for 1940) or "Sample Line" (for 1950).

In the image below, you will note the red arrow pointing to "Supp. Quest". The person whose name is written on that line, which is in this case a woman named Alice E. Hawley, has answered additional questions.

If you scroll down to the bottom of that census page, you will see the answers to the supplementary questions. These questions are asked to a sampling of the population, and not to everyone.

Below you can see some of Alice Hawley's answers to the extra questions asked of her.

It goes without saying that this extra bit of information can be very enlightening and informative for the lucky person who finds it.

This detail can help you know who is "talking"

Did you know that sometimes you can figure out who provided the information to the census taker? Knowing this information can sometimes help explain inconsistencies between the census records and other records that you have discovered for your family members.

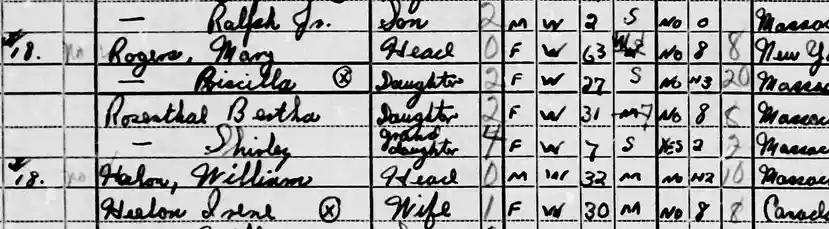

This was only customary on the 1940 census. The person who gave the information had a little circle with an x inside next to their name.

In this the image below, you can see two households. In the first household, Priscilla gave the information, and in the second, it was Irene.

Priscilla was the daughter of Mary Rogers, the head of household, in the first household list on this census record from 1940. She was living in Hampden, Massachusetts in this census record.

We often saw daughters and wives giving census information since the men and older sons were off at work. However, sometimes neighbors and children gave answers, which could explain why sometimes they don't match up with other information we have found about our ancestors.

Some census records might include an address

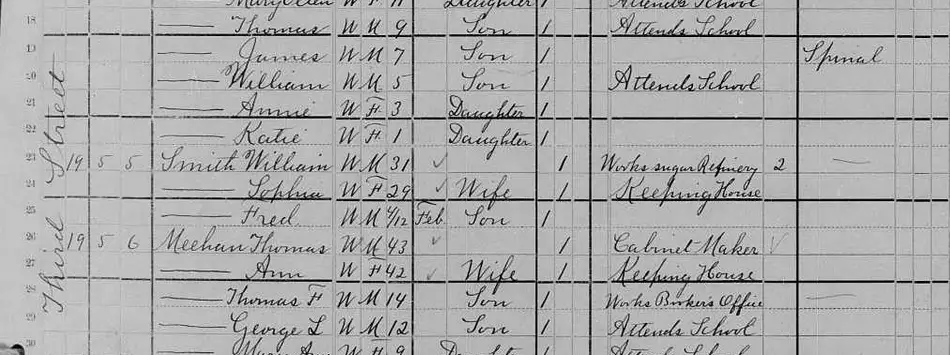

Sometimes, the census enumerator wrote the street name off to the left-side of the census form. If the street name is written on your ancestor's census record, you will see it written vertically across the entire left-side of the record.

If you inspect the image below from the 1880 census, you will see "Third Street" written in cursive on the left side of the page. Everyone who is on this section of the page lives on Third Street.

This information can be helpful because census enumerators usually recorded a house number along with census information. With the house number and street name, you are well on your way to finding out a great deal more about your ancestor's life.

Using this information, I have been able to use Google Maps to see photographs of at least two homes that my ancestors lived in during the late 1800s. Sometimes, you might get lucky and see what the inside looks like (more recently) on Zillow by typing in the address on that site.

Real estate sites like Zillow also include information about when the current home at that address was constructed. While it isn't always 100% accurate, it can help you determine whether the current home is the same place where your ancestor may have lived.

You can find out how much money your ancestor had

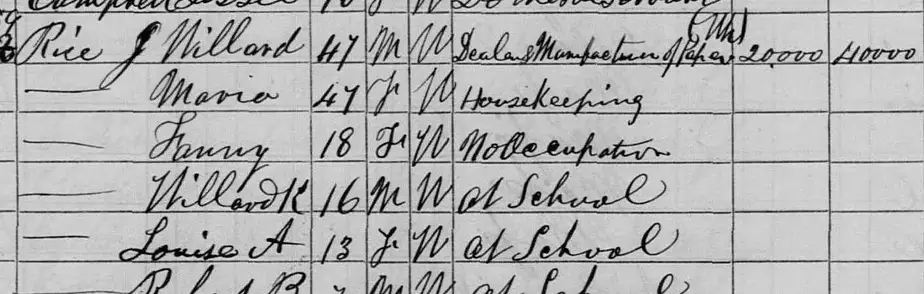

You might be able to discover a family fortune on the census records. Or in my case, a lack of a family fortune.

Some census years included questions about personal and real estate value. This information is included on the same line where your ancestor's name is written.

I included as an example one of the largest personal and real estates that I have seen on the 1870 census. His name was J Willard Rice, and the modest fortune that he reported to the census taker was $60,000, which is more than $1.6 million in today's dollars.

Apparently, he owned a paper manufacturing and distribution business in Massachusetts. I also had an ancestor living in this area in 1870, and he said he "peddled stationary" on his census record, so perhaps he was selling Mr. Rice's paper?

Census enumerators were instructed to only report personal property or real estate values if they were at least $100. My ancestor didn't have any value in the field next to his name, which indicates he likely did not have more than $100 to his name.

In the 1870s, wealth was generally concentrated in a relatively small group of people. Mr. Rice's personal estate of $60,000 was remarkable in 1870, since the average estate value of all property holders that year was $2,958.

The census could lead to discovery of additional records

Your ancestors' census records could help you discover additional records pertaining to their lives. You might learn about the likely existence of immigration, naturalization, military, and property records based off their responses to census questions.

Immigration records

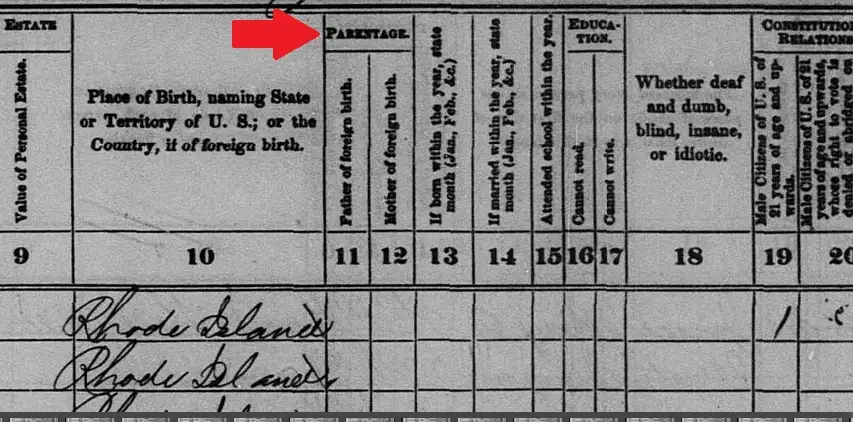

On the 1860 census, for example, questions about parentage were asked. The question was whether the respondents mother or father was of foreign birth.

If your US-born ancestor indicated that their parents were born somewhere else, this is a clue to look for immigration records for their parents. This column isn't something that everyone knows to look for, so definitely check it out if you have located your ancestors on the 1860 census.

If your ancestor said that their parents were born in another country, the column right next to their (your ancestor's) place of birth will have a tick-mark in it, as seen in the image below.

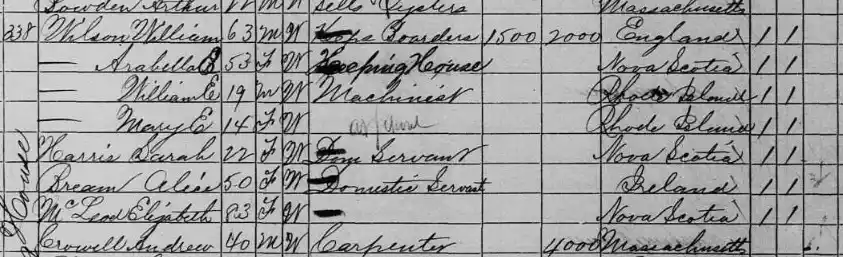

Everyone who lives in William Wilson's household has parents who were born in another country, including the two domestic servants and an 83-year old woman living in the home.

Property records

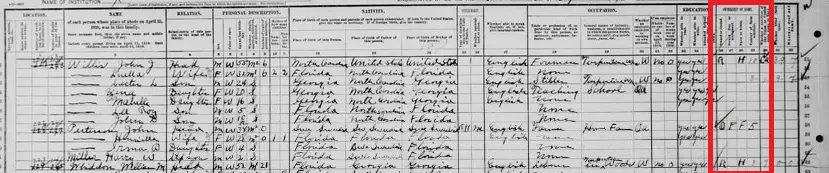

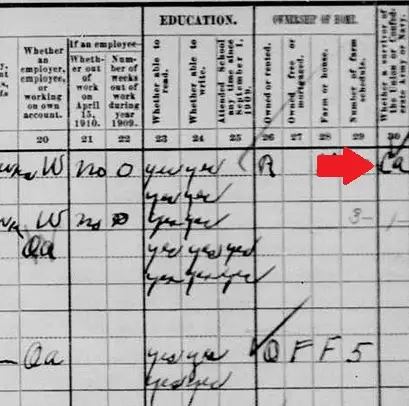

On the 1910 census, a question was asked about home ownership. This column is located far to the right of your ancestor's name, so it is easy to miss.

In the image below, the column with the answers to questions about home ownership is highlighted in red. If you have located an ancestor on the 1910 census, you would need to scroll all the way over to the right and zoom in in order to see these answers.

The census taker used codes to record responses for this question. If your ancestor owned their home, there would be an "O" in the column for owned or rented, and if they rented, there would be an "R".

In the image below, the first head of household indicated that they rent their home, and the second person owned their home. In this section, you can also see if your ancestor's property was mortgaged or owned free and clear, whether their home was a farm or a house, and the number of their corresponding farm schedule.

These are all potential opportunities to find more information about your ancestor somewhere off the census page.

Military records

Some of our ancestors may have fought in the military at some point in the country's history. Again on the 1910 census, if we scroll even further to the right, we can see a column with notations about military service.

In the image below, we see "Ca" written in the top column. This means that this person was a veteran of the Confederate Army. Union Army would be abbreviated "UA".

This census entry is for John J. Willis, born in North Carolina, who was living in Grassy Point (likely now Holmes Beach), Florida, aged 55. He says he is a survivor of the Confederate Army.

I did some math, since he seemed kind of young for a survivor of the Civil War. According to my calculations, he was ten or eleven in 1865, which seems very young to be a solider.

However, upon further research, it seems that children as young as 7 were permitted to enroll in the army on both sides, and soldiers as young as ten were very common in the south. They were different times, that's for sure!

Anyhow, for a descendant of Mr. Willis, which he should have due to the five children listed on the 1910 census, it would be interesting to learn the history and extent of his military service. The census record gives an important clue.

Your ancestor may have been related to a neighbor

You may frequently find that your ancestor was related to one of more of their neighbors. Check the surnames of people who are listed on your ancestor's census record, as well as on the page immediately before and after, to see if you recognize them.

I have also found instances where a nearby neighbor is a sister of my ancestor. Her last name was different from my ancestor's because she was using her married name.

It can be fun and enlightening to do a little research on the neighbors.

You might find medical insights

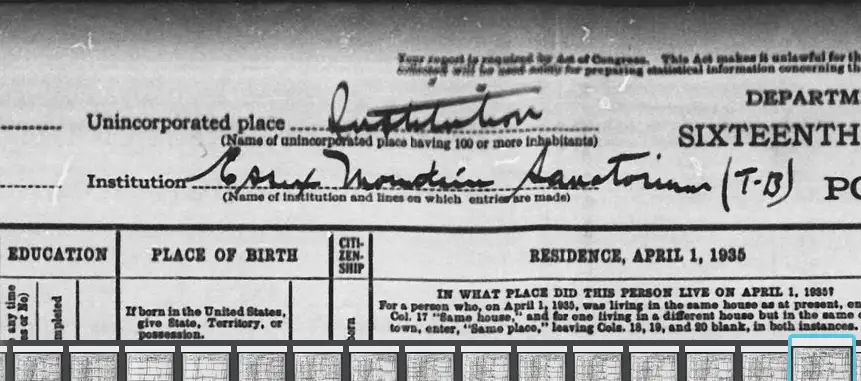

Census records can occasionally reveal medical insights about your ancestor's health and lifestyle. There are several different ways to find possible medical information on census records from different years.

For example, I found my great-grandfather living in the Essex Mountain Sanatorium where he had been hospitalized with tuberculosis. Unfortunately, my great-grandfather did not recover from his illness.

However, he did leave this paper trail for me to follow. Perhaps I can determine whether old patient records still exist.

You may be able to learn about your ancestor's health from clues found on census records. During my research, I have seen all sorts of health conditions documented in different ways on the census.

The enumerator may have been a friend, relative, or associate of your ancestor

Census enumerators often lived and worked in the areas that they canvassed while working their census jobs. This means that the census enumerator may have known your ancestor personally, and even could have been a relative or close friend.

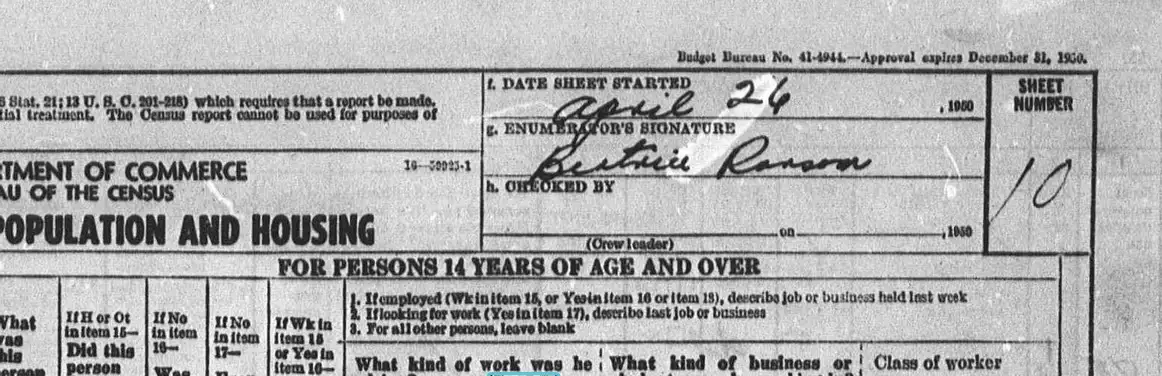

On the 1950 census, you can easily find the enumerator's name by looking in the top right corner of the page. In the image below, we can see that the enumerator's name for this census enumeration district in Egg Harbor, New Jersey, was Beatrice Ransom.

Beatrice Ransom was listed in the 1950 census as living in Egg Harbor, though someone else did the census for her neighborhood. Her occupation was indicated as census enumerator that year, and she was 28-years old, married to a storekeeper at a naval air base.

The population of Egg Harbor was just about 3,800 people in 1950, which is a pretty small town. Beatrice could have known, or been related to, any number of people who she questioned on the census.

Definitely look for the enumerator's name on your ancestor's census forms to see if you can do a bit of research to find a connection between them.

Conclusion

I hope that you have enjoyed this article about all of the surprises the census forms might have in store for you, and I hope you are inspired to take a second look at the census records that you've already found.

If you have any questions about something that you read in this post, or if you would like to share something from census records that surprised you, I would love to hear from you in the discussion below.

Thanks for reading today!